[Blankets, by Craig Thompson; chapter 1 & Understanding Comics, by Scott McCloud; chapters 1 and 2]

Thompson's Blankets is a little heartbreaking. It's the kind of thing I inevitably read, whether it's assigned or not: all soft but cutting underneath. "Cubby Hole," the first chapter, tells the story of Craig (the author) and his brother, Phil. They say the first sentence of any piece of writing is the most important to the reading of it. Thompson's first sentence fits the mode, saying, "When we were young, my little brother Phil and I shared the same bed." Being three years apart feels like a lifetime when you're a child, and Craig explains the gap he felt and sequentially made wider between his brother and himself. The only time they were (felt) close was in drawing and in exploring a forest behind their home.

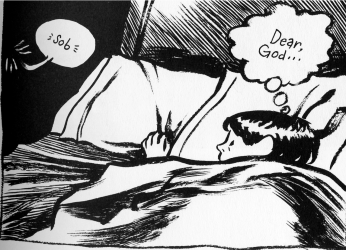

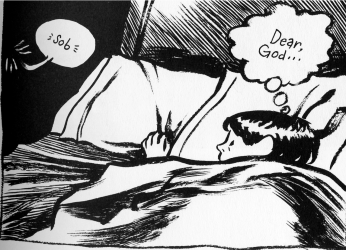

Craig is bullied at school, even through secondary levels, and tries to escape through drawing and dreaming (shown below). When he's older, though, he reads, "A profusion of dreams and a profusion of words are futile. Therefore fear God," from Ecclesiastes. He interprets this (wrongly or not, I don't know) to mean that "dreaming & drawing [are] the most secular and selfish of worldly pursuits." He burns all of his childhood drawing, and he tries to burn his memories with them. The chapter is bookended with Phil being locked in a hidden closet (the “cubby hole”) by their father, Craig unable to do anything about it (shown below).

[pages 42-43 from Blankets; Craig using dreams as escapism]

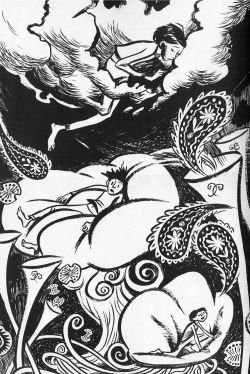

[pg. 65 from Blankets; Craig listening to Phil cry in the "cubby hole"]

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[pg. 65 from Blankets; Craig listening to Phil cry in the "cubby hole"]

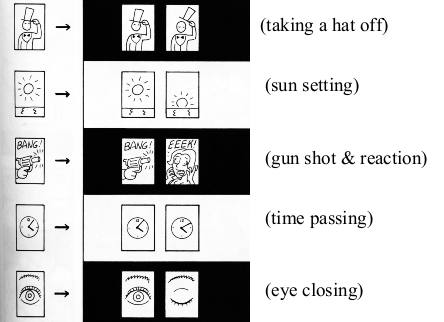

McCloud gives us a brief introduction to comics, spanning the background and different kinds. He also tries to come up with a definition. Staring with “sequential art” (shown below), he works off the two words to try to make comics something definable. He has trouble, in the form of a comic himself after all, and concludes that comics will always mean something different to everyone, every culture, and even every generation.

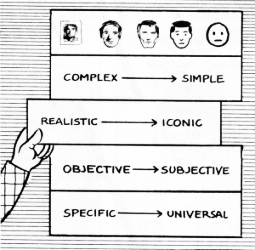

In Chapter Two, “The Vocabulary of Comics,” McCloud discusses icons and how they are used in comics to universalize the images (shown below). Humans are set up to recognize them/ourselves in everything around us-- to see faces and mouths when there art any; this is why there's a Man in the Moon. McCloud also addresses the relationship between writing a comic and drawing one. An artist and a writer must bridge that chasm to create an effective storyline. He presents an equilateral triangle, its base angles being "reality" and "language/meaning," and its peak being "the picture plane." Art is effectively the peak, nature the lower left, and "ideas" on the lower right. Artists and writers must find some feasible way of blending the three to create a comic without separating the words and pictures.

1 comment:

Soft but cutting underneath, I like that description of the book, it's really fitting. It is definitely something that I end up reading too, whether or not it is assigned.

Post a Comment